The Search for Better Digestion

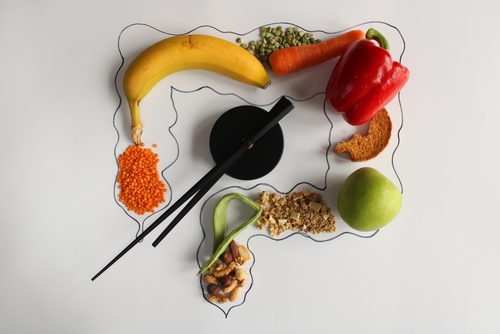

For anyone who’s dealt with bloating, sluggish digestion, or that heavy feeling after meals, the idea that how we eat might be just as important as what we eat can be intriguing. Enter the concept of food combining—the idea that certain foods digest better when eaten together (or separately), and that meal timing can impact everything from energy levels to nutrient absorption.

While some of the more rigid rules of food combining diets are debated, there’s growing interest in how meal sequencing and timing may influence digestion, especially for those with sensitive stomachs or lingering gut imbalances. Let’s take a closer look at the theories, the science, and what gentle adjustments might actually support better digestive flow.

Ad Banner #1

— Placeholder for the first advertisement —

What Is Food Combining?

At its core, food combining is the practice of eating certain types of foods together—and avoiding others in combination—with the goal of improving digestion and nutrient absorption. These guidelines are rooted in the belief that proteins, fats, and carbohydrates require different digestive environments and enzymes, and when eaten together, can lead to slower digestion, fermentation, or discomfort.

Common food combining principles include:

-

Eat fruit alone, especially on an empty stomach.

-

Avoid mixing proteins with starches (like meat and potatoes).

-

Don’t combine acidic foods with starchy foods (like tomatoes and pasta).

-

Wait several hours between meals of different macronutrient profiles.

These ideas gained popularity in the early 20th century and have seen waves of renewed interest through various wellness movements. However, most mainstream nutrition science doesn’t support all of these rules across the board—especially for individuals with healthy digestion. That said, some principles may be worth exploring, particularly for those dealing with digestive discomfort, bloating, or sluggish elimination.

Digestion: A Coordinated Process

Digestion is a complex, beautifully orchestrated system that starts in the mouth and ends in the colon. When we eat, the body releases enzymes and gastric juices based on what’s detected in the food. Proteins trigger the release of stomach acid and pepsin, while carbohydrates require different enzymes (like amylase) and tend to digest more easily in a slightly alkaline environment.

For people with a healthy gut and strong enzyme output, mixed meals are typically handled without trouble. But for those with imbalances—low stomach acid, slow motility, or gut inflammation—simplifying meals or sequencing them more thoughtfully might ease the digestive burden.

Timing and Meal Sequencing: What Matters

Beyond combining food groups, meal timing and sequencing can also influence how comfortably and efficiently we digest.

1. Start with Light, End with Dense

It’s often helpful to begin a meal with lighter foods (like leafy greens or a raw veggie starter) and move toward heavier proteins and fats. This mimics the body’s natural digestive rhythm and can reduce bloating.

2. Give Fruit Its Space

Fruit digests quickly—sometimes within 30 minutes. When eaten on top of a heavy meal, it can linger in the stomach, potentially leading to fermentation and gas in sensitive individuals. Try enjoying fruit on its own or at least 30–60 minutes before other foods.

3. Avoid Heavy Late-Night Eating

Eating large, rich meals late at night can disrupt digestion and even sleep. Aim to finish eating 2–3 hours before bed to allow the stomach time to process the last meal before the body shifts into rest-and-repair mode.

4. Honor Gaps Between Meals

Spacing meals 3–4 hours apart (rather than constant grazing) gives the digestive tract time to reset. During fasting periods, a process called the migrating motor complex helps sweep out waste and reduce bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine.

Ad Banner #2

— Placeholder for the second advertisement —

What Does the Science Say?

Scientific research around strict food combining is limited, and the digestive system is generally well-equipped to handle mixed meals. However, there is support for certain aspects of timing and sequencing:

-

Meal frequency and spacing: Studies suggest longer gaps between meals may support motility and reduce bloating.

-

Circadian rhythm and digestion: Digestion tends to be more efficient earlier in the day. Heavy meals late at night are linked with slower gastric emptying and potential reflux.

-

Enzyme efficiency: In people with impaired digestion (low stomach acid, enzyme insufficiency), simplifying meals may reduce symptoms like gas and indigestion.

So while strict “don’t mix carbs and protein” rules may not be necessary for everyone, tuning into when, how, and in what order you eat may still make a meaningful difference—especially if you’re navigating digestive discomfort or healing your gut.

A Gentle, Personalized Approach

Rather than following rigid rules, use food combining as a flexible framework. If certain combinations seem to weigh you down, try spacing them out or adjusting the order in which you eat. Track how you feel, and let your body be your guide. Some people may thrive on mixed meals, while others may feel better with simpler pairings.

Simple habits to try:

-

Begin meals with greens or broth to “prime” digestion.

-

Enjoy fruit on its own in the morning or as a light afternoon snack.

-

Keep evening meals light and stop eating a few hours before bed.

-

Experiment with mono meals (one main food group) during times of digestive reset or illness.

Final Thoughts: Your Gut, Your Rhythm

The gut doesn’t need to be micromanaged—but it does respond to rhythm, routine, and respect. Food combining and meal timing may not be miracle solutions, but for many, they offer subtle shifts that lead to real relief. Listening to your body’s signals—fullness, bloating, energy—is often more powerful than any one-size-fits-all chart.

Start with curiosity. Observe. Adjust. And over time, you’ll develop a meal rhythm that supports both comfort and nourishment.